Classic newspaper headlines:

“Giant Waves Down Queen Mary’s Funnel,”

“MacArthur Flies Back to Front”

“Eighth Army Push Bottles Up Germans”

“Squad Helps Dog Bite Victim"

“Red Tape Holds Up New Bridge”

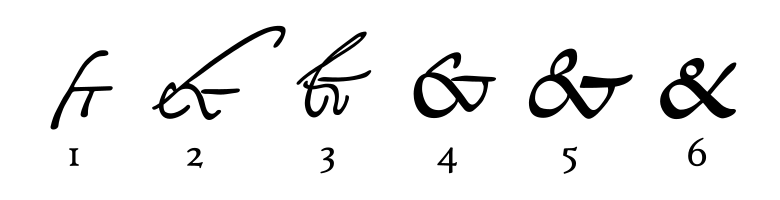

For years, there was no good name for these double-take headlines, Ben Zimmer

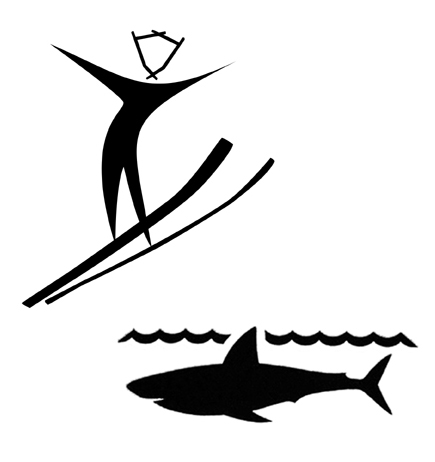

writes in The New York Times. Last August, however, one emerged in the Testy Copy Editors online discussion forum. Mike O’Connell, an American editor based in Sapporo, Japan, spotted the headline “Violinist Linked to JAL Crash Blossoms” and wondered, “What’s a crash blossom?” (The article, from the newspaper Japan Today, described the successful musical career of Diana Yukawa, whose father died in a 1985 Japan Airlines plane crash.) Another participant in the forum, Dan Bloom, suggested that “crash blossoms” could be used as a label for such infelicitous headlines that encourage alternate readings, and news of the neologism quickly spread.

Zimmer has more:

“McDonald’s Fries the Holy Grail for Potato Farmers”

“British Left Waffles on Falklands”

“Gator Attacks Puzzle Experts”

How do we explain crash blossoms?

Zimmer: Nouns that can be misconstrued as verbs and vice versa are, in fact, the hallmarks of the crash blossom. English is especially prone to such ambiguities. Since English is weakly inflected (meaning that words are seldom explicitly modified to indicate their grammatical roles), many words can easily function as either noun or verb. And it just so happens that plural nouns and third-person-singular present-tense verbs are marked with the exact same suffix, “-s.” In everyday spoken and written language, we can usually handle this sort of grammatical uncertainty because we have enough additional clues to make the right choices of interpretation. But headlines sweep away those little words — particularly articles, auxiliary verbs and forms of “to be” — robbing the reader of crucial context. If that A.P. headline had read “McDonald’s Fries Are the Holy Grail for Potato Farmers,” there would have been no crash blossom for our enjoyment.